“Today is the Day We Live”: Willa Dallard, one of SK’s Pioneering Settlers of African Descent

This article was originally published in the Spring 2015 edition of Folklore Magazine. It was updated for this blog post.

Imagine if the only chance you could get to create the life you envisioned for yourself and your family required you to move far away from home. Imagine knowing that staying may mean perpetually looking back and wondering if you might have lived a fuller life, if you had worked up the courage to pack up your life, family, children, hopes and attachments -and leave for a distant, seductive, yet unknown future. What would you do?

Now imagine if that journey meant that you would manhandled at the border, treated patronizingly by well-meaning neighbours, and pitied by classmates. And that you would arrive to a country where the Prime Minister would be pushing for regulation to ensure that people who looked like you could not come into the country. It might sound like a story from very far away. But it is not more than hundred years ago, when this was the experience of Willa Dallard, one of the earliest black settlers in Prelate, Saskatchewan.

Willa Bowen Dallard in 1982. Photo courtesy of Brenda Zeman, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan R-A23391.

In her two-part memoir, Memories of My Father, she tells the story shared by many of the early black settlers of Canada that left the United States in order to have a chance at freedom and to be judged on their merit and not their skin color. Because they had the freedom to get land and exercise their civil rights in the Indian Territory, African-Americans were drawn to settle there. However, this freedom was short-lived.

By the time this territory had become the state of Oklahoma in 1908, it was dominated by an increasing population of white Americans who had moved from the older southern states and brought their segregation policies with them. By 1910, most of the newfound freedoms of the African-American settlers, including their right to vote, were taken again by the white majority through a state-wide referendum. As a result, while technically free to own property and exercise their rights, they faced impossibilities in doing so.

In response to the growing racism in the newly formed state of Oklahoma, Willa's family moved to Canada "to go where every man was accepted on his merit or demerit, regardless of race, colour or creed."

But they would find that coming to Canada did not quite solve the problem of racism. In Willa's words, "I noticed that when we boarded the train to Guthrie, Oklahoma, the farther north we got, the less Negroes we saw at the stations and on the streets we passed. By the time we got to the line, there were none at all. It was then I began to learn what it is like to be a Negro in a white world."

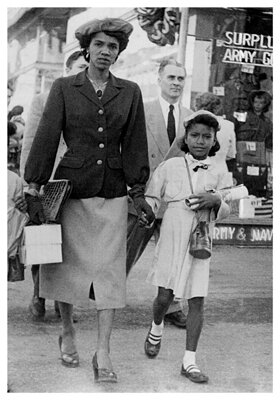

Willa (right) and daughter Phyllis. Source: Edmonton Public Library.

As the Saskatchewan historian Bruce Shepard chronicles in his book Deemed Unsuitable, in which he explores the social and historical realities which these early settlers had to encounter, being “a Negro in a white world” was quite difficult in Canada as well. White Canadians were said to not have been as confrontational about their racism as those living in America, yet they were all the same. In response to sudden influx of black people, the Laurier government drafted a regulation to stop their entry.

Having been refused entry originally, Willa's family was eventually able to secure entry through another border. By this time, they had lost relatives and property in the course of migration due to natural disaster, sickness, and disease.

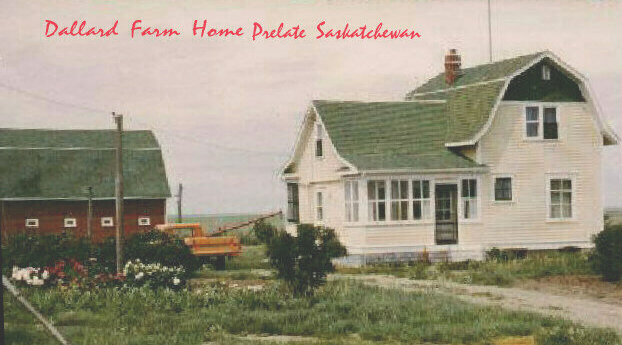

They finally settled in Edmonton. Willa's journey did not stop there, however. She met and eventually married Noah Dallard, a young man who had made a good impression on her father and brother. On a cold winter day, she moved again with him in what she recalls jokingly as the equivalent of a honeymoon—the long and freezing journey to Prelate where they acquired a farmhouse and started a family. At this house they lived out their years as grain farmers, with some farming years having more yield than the others. They also raised their four children here.

Dallard farm home. Image source: genealogy.com.

Willa, intent on ensuring a musical education for her children, exchanged cream and milk at the convent in exchange for piano lessons for her children. She would later recall the good old days of the small close-knit community in Prelate before intense urbanization. Yet, this spatial distance from everything did cost her daughter Cora Jean's life, who died at ten due to a ruptured appendix, which the doctors were unable to operate on in time because the nearest hospital was forty miles away.

Tragedy would strike her and her husband again after her son Kenneth drowned in a boating accident. A Second World War veteran, she had recalled that though Kenneth came back home in perfect physical condition, his inner life had been traumatized. Within a year of his return home, he drowned in a motorboat accident at the ferry in Prelate.

Due to these hardships, as well as the responsibilities on the farm, her husband became sick and died as a result of the combined complications of diabetes, high blood pressure, and cancer. She often wondered how these experiences drew her closer to her faith, when they could quite as easily have pushed her away from faith. However, she drew from this faith to make sense of her losses, comparing her crushing experiences to the rose which has to be crushed to extract the fragrance.

The Prairies changed very much from Willa's early homesteading days and she bore witness to this in her writing. She noted the changes that rural Saskatchewan saw as it began transitioning from an agrarian community to an industrial age where mechanized agriculture made subsistence farming infeasible for men with small farms.

This change had implications on the lived experience of the prairie dwellers. As a result of this transition, people started selling or renting their lands and taking up working opportunities instead. The exodus of the small farmers also affected the economic landscape; small local schools, churches, and businesses were closed—instead people traveled to larger towns and the city to fulfill these needs. Soon doctors, hospitals, drug stores, and grocery stores also moved to the city.

Phyllis and her daughter, Gloria, in 1954. Photo courtesy of author.

Willa told her story of being one of the first black settlers in a video account, which is available at the Washington University library and the University of Toronto library, and in several newspaper articles reciting her lived experiences in those early days. Donald, her second son, was left to farm their land until he retired and moved to Medicine Hat, Alberta. Phyllis, her daughter (fondly known as PJ), eventually lived in Edmonton, preserving the historic items from their early days on the prairie in her apartment.

Reflecting on her life's journey, Willa ends her memoir with the following simple but resonant reflection:

“In the maze of life we all wonder which way should I have turned. Only God knows. I only know that I have lived a very full life, not placid, mind you but with my full share of its ups and downs to make it interesting to say the least. So at my age there isn't too much to look forward to, but there are a lot of memories. And to look back is sometimes painful. Lot's wife looked back and turned to a 'Pillar of Salt'. So, in conclusion, I will say: Yesterday Has Passed, and Tomorrow Never Comes, Today Is the Day We Live."

For more on Willa Dallard, see her profile at the Saskatchewan African Canadian Heritage Museum (SACHM).

Willa Bowen Dallard and her daughter Phyllis Dallard Johnson, descendants of black settlers in Saskatchewan, photographed at Fiske in 1982 by Brenda Zeman. Photo courtesy of Brenda Zeman, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan R-A23391.

Ebele Mogo.

EBELE MOGO is a storyteller, a scientist, and an innovator. Her writing has been published in the following places: Newfound, Third Point Press, Munyori Literary Magazine, Stockholm review of literature, Susan the Journal, The Offing, Saraba magazine, Tap Lit, Narrative Northeast, Brittle Paper, the Rising Phoenix, Interartive, among other places. She is on Twitter as @ebyral.

Call for Writers

On SK African-Canadian History

Do you have a story you’d like to share?

Contact Kristin Enns-Kavanagh, Executive Director, at 306-975-0826 or info@shfs.ca. Writer payments available. Option to publish anonymously.

“people stories” shares articles from Folklore Magazine, a publication of the Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society. Four issues per year for only $25.00! Click below to learn more about the Magazine or to find out how to get your story into the blog!