Growing Up on Saskatoon’s Road Allowance

This story was originally published in Lii Mimwayr Di Faamii (Family Memories), a compilation of stories from members of Gabriel Dumont Local 11, a Métis Local in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. The work began as oral stories, recorded over Zoom during the pandemic. The stories were then transcribed and edited into a Special Edition of Folklore Magazine, published in December 2021.

Lii Mimwayr Di Faamii.

Click below to watch the original video of Nora Cummings sharing this story:

It’s quite an honour for me to tell my story as a Road Allowance Métis. I was born in Saskatoon on January 1, 1938 and we lived close to where Aden Bowman Collegiate now stands. At the time, that land was owned by the City of Saskatoon but it was considered the outskirts of the city. Métis families were the only ones that lived there. We didn’t own the land. It was a Road Allowance community.

There were over thirty-five Métis families living there. Their names were Trotchie, Ouellette, Landry, Vandale, Fayant, Letendre, and others. Some Métis women married non-Métis, so families by the name of Camponi and Birmingham were also part of our community. These were all Métis families that had moved from the Round Prairie Settlement south of Saskatoon.

Nora Cumming’s mother’s family taken at a cousin’s funeral in the Road Allowance community near Lansdowne Avenue, near where Aden Bowman Collegiate now stands. Back Row L-R: Norman Trotchie, Irvin Trotchie Middle Row: Clarence Trotchie, Violet (Trotchie) Livingstone, Alex Trotchie Front Row: Louise (Trotchie) Belcourt, Justine (Landrie) Trotchie (Nora’s Grandmother), Irene (Trotchie) Dimick (Nora’s Mother). All photos courtesy of author.

Our family lived on the Road Allowance until 1953 when we were forced out and had to move into the developed area of the city. It was quite a shock for most of us because that was our community and that was where we all lived. It was the community we knew, with our mooshums and kookums, aunties, uncles, cousins, and our Old People.

Phyllis (Trotchie) Vance, Violet (Trotchie) Livingstone, unidentified, unidentified, Fred Wells in front of Three Sisters (the three houses in the background) on York Avenue in Saskatoon, ca. 1950s.

When the families moved into the city, they had to adapt and find places to live. It was a sad time because in the city they lived more spread out from one another than when we lived on the Road Allowance. Our families never had that same kind of closeness as when we lived all kind of mushed together on the Road Allowance.

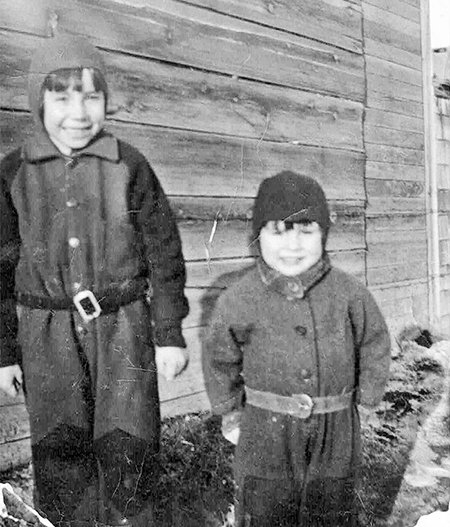

Nora and her sister Phyllis, taken at the Road Allowance community, Lansdowne Avenue area.

Road Allowance shack, 1951. Nora lived in this tent and little house on First Street East in Saskatoon (about 900 block).

On the Road Allowance we lived in a little shack down by First Street not far from the intersection on Taylor and Clarence Avenue. Clarence Avenue was the old highway then. There were five of us that lived in that little house. My mother’s name was Irene Trotchie and my dad was Jerome Ouellette, but he was called Jerry.

Nora’s parents – Jerry Ouellette and Irene (Trotchie) Dimick, taken on Avenue G South in Saskatoon.

We used to hunt deer and snare rabbits. We picked our berries. We used to harvest all that stuff and do things for ourselves. We had a community garden where Aden Bowman Collegiate now stands and everybody would plant vegetables and potatoes.

We all took turns cleaning the gardens and looking after it. In the fall we’d all harvest. We had little dug out cellars under our shacks where we’d put our vegetables so they would stay fresh.

I remember that everyone worked really hard. I worked with my dad. I drove my own team of horses. I was always proud of my horses because I was able to drive them by myself and help my dad. I was the second oldest. My older sister wasn’t interested in working with my dad and my brother was too young.

In the summer we would go out and work for farmers around what is now the Sutherland neighbourhood. We would all pitch our tents and live there for the season. My dad and I cut and stacked hay for the farmers. My uncles all picked stones and cleared farmers’ fields. After a while I had to stop working with my dad because my grandmother wasn’t well and it became my role to look after her.

Clarence Trotchie.

My mother also worked. She cleaned the homes of doctors, lawyers, and others that lived on Saskatchewan Crescent. I remember her coming home so tired, but she never ever gave up. She never quit working because her income was important for us. She had a little bike and I remember her being the best little bike rider in Saskatoon. She could handle that bike really well. That’s how she got to work.

Nora’s mother Irene (Trotchie) Dimick at 915 – 2nd Street East, Saskatoon, 1952.

I had three cousins that were similar to me in age. We were the older ones. We all had to work. We used to go out and get water from the slough and haul water into the house to make sure we had enough for washing clothes. Sometimes in the winter, we had to bring in the snow and melt it for laundry. That was our job. My role was to look after the Old People and help take care of the young babies and my young cousins.

Nora and her brother and sister. Nora in front, Phyllis in back, Chick (named Lloyd) on 2nd Street, 1950s.

We never really felt that it was hard work, it just came natural to us because that’s the teachings we had and everybody had work to do. At the time, I didn’t think it was a hard life because I was young. You don’t think that way when you’re young, but when I sit back and I think today, I remember how hard everyone worked to survive.

I also remember going on picnics when I was young. They used to hook up our wagons on a Sunday and the women would make a great big lunch. We’d all get together. We’d go past Moose Wood Reserve. It’s called Whitecap now. We’d go and picnic out there by Round Prairie. We played baseball and horseshoes and we had big sacks or bags to hop in. We had all kinds of activities.

Sometimes I think about those days living on the Road Allowance and how those picnics were a way for us to get away from all the stuff that was happening in our lives. They were a time to get together, visit and have some fun and be with all our relatives.

Clarence Trotchie, holding Gary Vance (Nora’s sister Phyllis’ baby) and Nora Ouellete on 2nd Street (900 block), 1952 or 53.

As I got older I lived with my Kookum. She had her own little house. She had cupboards made out of apple boxes. That was our mansion, and we enjoyed it. Most families lived in similar shacks, and in the summer, some of our people moved into tents. Kookum brought me up, so I was the fortunate one that had lots of good teachings.

Justine (Landrie) Trotchie – Nora’s grandmother. Location: on the Road Allowance – taken the same time as the first photo in this article.

She was seventy-five when she passed away. I lived with her and looked after her and never regretted it because she was my mentor and my teacher. She taught me my culture, my language, my understanding of what life was about. We learned from the Old People. They were our teachers. I always wondered how she managed. She had lots of children. Eight that lived.

I chopped wood for my Kookum. That’s how we heated our shacks in the winter. It was a lot of work to chop wood. Most of my cousins and my uncles would all take turns and we’d stack it all up for her for the winter. My Kookum would pick up the little chips because she used to think they were good to start the fire. I remember one time when I took a photo of my Kookum with my auntie’s old box camera. My Kookum got so mad at me for taking that picture. I remember her giving me heck because of it. But I always liked that picture because I thought she looked so cute sitting out there trying to collect all those little wood chips.

Nora’s grandmother Justine (Landrie) Trotchie picking up kindling. Taken on the Road Allowance, 2nd Street, 1950.

My Kookum spoke in very broken English. If she went somewhere where there were people she would talk to me and I’d have to translate for her because she felt that people would laugh at her. It took a long time but we got her to feel comfortable and not ashamed to speak when we would go out.

Nora Ouellette and her Grandma Justine Trotchie on 21st Street, Saskatoon, 1953.

One time when we lived out in the bush, I had to clean the house for my Kookum and used to haul everything out of our shack so that I could scrub and clean the floors. My Kookum was sitting outside in a big chair surrounded by all our stuff, and all of sudden she called, “Ashtum ota!” (Come here right away).

I went outside and here my friends had come to visit. I had big curlers in my hair, and was dirty from scrubbing floors. Everything from our house was sitting outside. I never forgot that because I thought it was so funny. I was proud of where we lived because that’s who we were, but when I think back I wonder what they thought. They never ever said anything but it was kind of funny.

When my Kookum first moved into the city from the Round Prairie Settlement she lived in a house at 1510 Broadway Avenue with all her seven children. My grandpa left and went and lived with another woman on the west side of town. Some of the families from Round Prairie had also moved to the west side of the city. At that time they used to have relief agents that would come around and give out tokens for food. If others came to visit and the relief agents found out, your relief would get cut off. That really bothered most of our people. That’s why some of our families moved to the Road Allowance.

I went to Day School. It was called St. Joseph’s School at that time. All the Métis kids went there. We didn’t have much schooling. I quit at an early age because of the abuse we went through at the school. I got married and had my own children. So that’s my story.

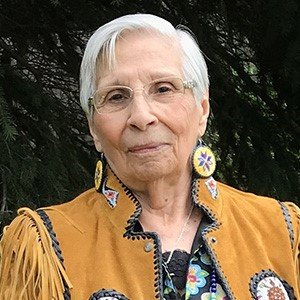

Nora Cummings.

Born and raised in Saskatoon, NORA CUMMINGS has been involved with the promotion of Métis rights and culture her entire life. In 1969, she was a founding member of Gabriel Dumont Local #11 and became one of the Métis Society’s first field workers and family advocates. She was a founding member of the Saskatchewan Native Women’s Association and was the first woman on the Saskatoon Indian and Métis Friendship Centre Board of Directors. Nora continues to be active in Gabriel Dumont Local #11 and is a Senator of the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan. She is an active member of the Saskatoon community and was involved in the dedication of the Saskatoon Public Library’s Round Prairie Branch, named for the Métis settlement south of Saskatoon of which she is a proud descendent. She was instrumental in the creation of a Saskatoon City Transit bus shelter honouring Métis history, culture, and heritage and a series of downtown bike racks that display Métis symbols.

Acknowledgements

The Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society is tremendously grateful to the members of Gabriel Dumont Local 11 for sharing their stories in Lii Mimwayr Di Faamii (Family Memories). Particular thanks go to Cheryl Troupe, Wilfred Burton, Susan Shacter, and Donna Heimbecker for editing the stories. Thanks also to Marcel Petit of m.pet productions for editing the videos.

“people stories” shares articles from Folklore Magazine, a publication of the Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society. Four issues per year for only $25.00! Click below to learn more about the Magazine and to find out how to get your story into the blog!