From Prairie to Prairie, Part I: Leaving Vietnam

As told to Hannah Tran by Ba Hung Tran.

This is the first in a two-part series recounting Ba Hung Tran’s memories of coming to Saskatchewan as a young man in the 1970s. Although this first part does not take place in Saskatchewan, it represents a history shared by many of this province’s Vietnamese people and their families and, therefore, provides valuable context to the upcoming parts of this story as well as Saskatchewan history in its own right. This series was originally published in three parts in Folklore Volume 44 Nos. 2, 3 & 4 (Spring, Summer, and Autumn 2023).

In Canada, my name is Ba Hung Tran, but in Vietnamese, you would say it backward: Trần Bá Hùng. I was born in Vietnam in a city called Vĩnh Bình, but when I was a year old, we moved to a city called Mỹ Tho. This story is about real life, so in a way, it’s sad and tragic. It is not glorious, but the truth is always the truth.

My family started with my father, who was born in the North, in Hà Nội , the capital of Vietnam. In 1954, the Communists took over the North, and my father ran away to the South. My father was in the French army fighting against the Communists. But even though we considered the Communists the bad guys, the French were the bad guys too, because they were invaders who had turned the country into a colony. So, my father could be considered a traitor, but the truth of that situation depends on how you explain it, because the real reason why he joined the French army was to escape poverty.

My mother was born in the North, in Hải Phòng, the second biggest city there at the time. At that time, the North was worse than the South, and the society was really sexist. They treated women like animals, and when my mother was young, her family lied to her. She begged them to let her stay in school, and they told her that she could, but then they took that away. She only got a grade 2 education—that’s how sexist it was, because, you know, women didn’t need education. She couldn’t stand it, and so she ran away from her family when she was 18 and ended up in the South, too. She started to have second thoughts, because she felt very lonely, and she realized that it was hard to be around others who had higher education, but she couldn’t go back, because she had already applied to go to the South, and she could not get another form to go back to the North.

So, my mother ended up in Saigon, where she met my father. They got married, but they never had a wedding. They didn’t even have a bed after they got married—they just slept on the floor. Because my father was in the army, they moved around to quite a few places, but it was in Vĩnh Bình that my older sister and two of my older brothers were born. I was born in Vĩnh Bình too, but we moved to Mỹ Tho after that, and my two younger brothers and one younger sister was born there. I had a total of six siblings, and I was exactly the middle child.

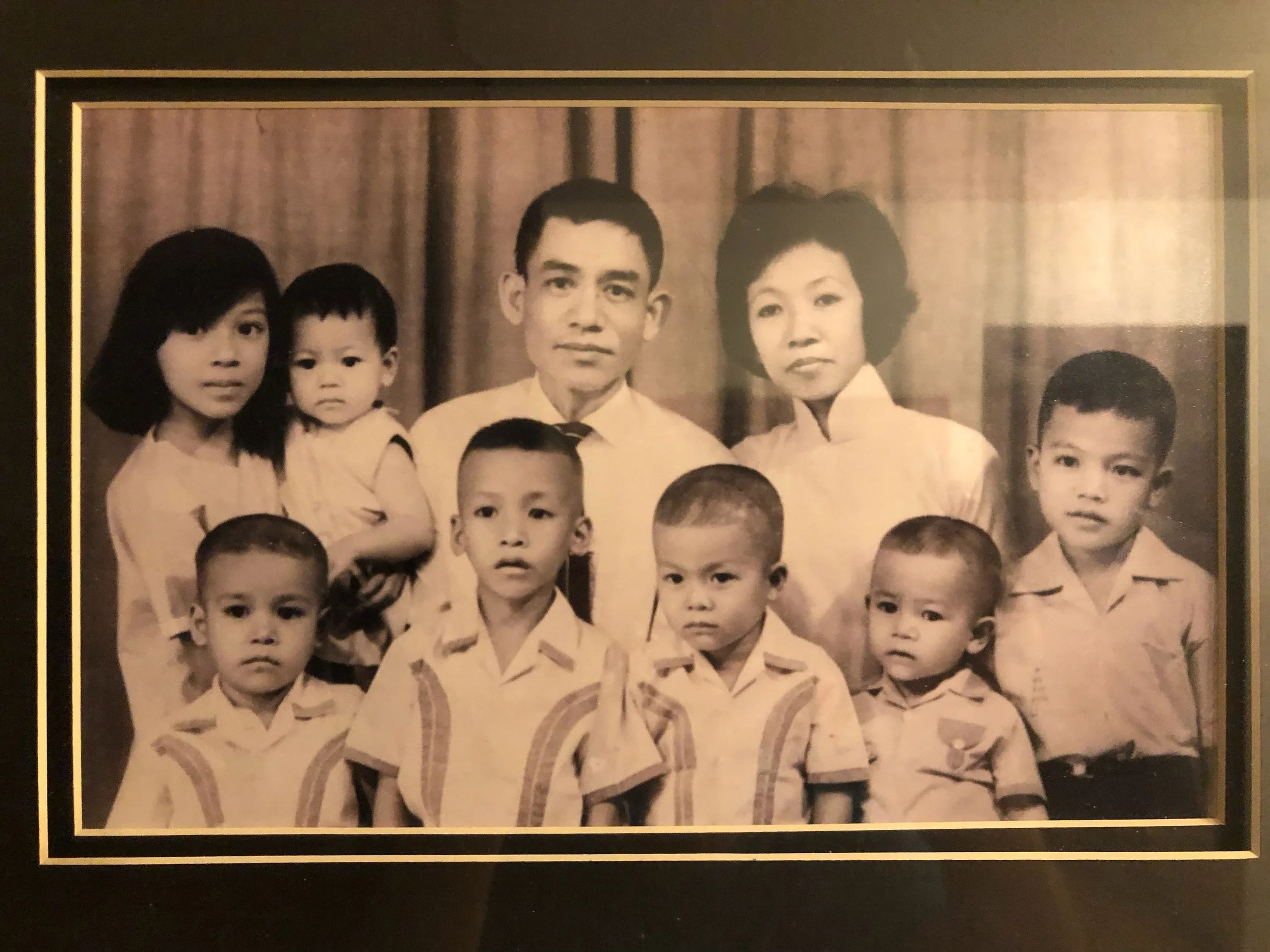

My family (circa 1970) from left to right: Back row, Tran Thi Thu Ha, Tran Thi Giang Huong, Tran Ba Dam, Nguyen Thi Lien. Front row: Tran Ba Hung (me), Tran Ba Hau, Tran Ba Hien, Tran Ba Vinh, Tran Ba Hung (older brother). My name written in Vietnamese: Trần Bá Hùng. My older brother’s name: Trần Bá Hưng. Our two names are different, but when spelled in English they appear the same.

In 1975, the Vietnam War ended, and the North took over the entire country, so we were under the control of the Communists, and our new government was horrible. My father was sent to prison as a political prisoner, which they called a re-education camp. I was the one who biked him to the camp on my pedal bike, and the government said that he would only stay there for four months, so he did not bring anything with him. But I was there, and I was crying when I said goodbye. I was very young—only 13 or 14—but I was able to tell him goodbye in a way that didn’t mean forever. It just meant that it was going to be quite some time. He ended up in there for two years, which was not that long, but it felt very long to my family. One of my older brothers was also sent to prison, and at that time, there was a chance that he could have died there, but he didn’t.

After that, I remember seeing my older sister talking to my mother and crying, because my mother had asked her and my older brother to quit school to help our family. I had to help my family too, by going to the open air flea market to help my mother with her sales.

Then, in 1978, people started to escape the country, and those people were known as the Boat People. I was one of those boat people, and I escaped in 1980 with my older sister and two of my brothers. I actually escaped three times, while my whole family escaped twice, but it was the third time that stuck—and only half of us made it. At that time, the decision was made that my parents would keep the two youngest children while they waited for my brother in jail. My parents were afraid that they would end up alone, so it was only the four of us.

I escaped with my sister and two brothers on October 2, 1980. We were in a narrow, ten-meter-long boat with forty-eight other people. At about eleven pm, we all got into the boat and headed for the ocean. It took about an hour to get there. When we reached the ocean, a storm came up. It was a small storm, but the boat was small, and it rolled up and down like a roller coaster. During the panic, the adults told us to throw everything overboard, because they were afraid the boat would sink. It was raining and pitch black, so we threw away whatever we could grab – including our food and water. When the storm died down, we realized we had enough food and water for one more day. It took ten days to reach Malaysia. For eight of those days, we had no food. It was the first time in my life I had gone without food for eight days. Luckily, it was the rainy season, so we still had water. After a long time, we saw a tiny island in the distance, and were told it would take a day to reach it. Eventually the water began to change its blue color because we were getting closer to land. On October 12, we arrived in Malaysia. Eventually, the UN came and took us to the refugee camps.

That is how we ended up in Malaysia in a refugee camp—or rather, two camps. The first camp was on an island in the middle of the ocean, called Pulau Tengah. Although the camp is not there anymore, the island is. And after we were accepted to live in Canada, we had to move to a transit camp called Sungei Besi A, which was named after a city in the area. Sungei Besi A was for people who were going to Canada, the United States, and Australia, while the other camp was called Sungei Besi B, and was for people who were going to live in Europe.

Us in the refugee camp. From L to R: Tran Ba Hien, Tran Thi Thu Ha, Tran Ba Hung, Tran Ba Hau. Note: These clothes were bought in Vietnam and worn when the family escaped, and in the refugee camps. They brought them to Canada with them and still have them to this day. The clothes have small white spots on them from being soaked in seawater on the crossing to Malaysia. Once when Hannah was in high school, she borrowed her dad’s shirt to play a hobo in a play. Everyone wanted to know where she got the shirt from, so she asked her dad where the shirt came from, and he told her the story. It was rare to have a camera in the camps, but Ba Hung had a friend whose family had sent him some money, so he had a camera and took the photos. He was a professional photographer. He was the original owner of the Red Pepper restaurant in Saskatoon (the second generation runs it now).

Like many other refugees, we faced an uncertain future in that we didn’t know what would happen to us. We didn’t know how long we would be stuck in the camp or where we would end up. At that time, there was an ongoing crisis, because within a period of about 5 years starting 1978 there was estimated one million people who escaped from Vietnam (and about half of them didn't make it), and the world didn’t know what to do with us yet. At some point, the United Nations had a meeting, and they built camps for us around Asia in Malaysia, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia. So, like us, many people ended up in Malaysia.

Now, the reason I ended up in Canada has to do with the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War. At the time, Ronald Reagan was not the American president yet, but he was campaigning to be, and one of his promises had to do with the Vietnam War and the Vietnamese refugees. He said that if he was elected president that he would bring back the bodies of the American soldiers who died in Vietnam back to the States. His second promise had to do with the Boat People. He said that if he was elected President of the United States, he would solve that problem, and he urged his allies to help him. So, when he was elected president, the first thing he did was he took 50,000 Vietnamese refugees to the States. After that, other Western countries including Canada followed suit, and suddenly, every country was coming to the refugee camp to help us settle in a second country.

When we were at the camp, we didn’t have a choice as to where we ended up. The way it worked was like this: when we were there, people who we called the delegation—or immigration—would come. We didn’t know when they came, we didn’t know which country would come, and we didn’t know how many people they would take. Sometimes when they came, they would have a whole pound of people’s files, and then they would only interview half of them before they would say that they were done. From what I understood, it’s because they couldn’t take all of us, since they had a budget to think about.

But one thing I remember is that you had to see the Americans first. There was a joke that it was because they wanted to take the good refugees, and then the leftovers would go the rest of the world, which was somewhat true. So, if you got accepted by the Americans, then that was fine, but you had to be rejected by them to apply to go somewhere else. Another way that you could end up in the United States was that if you just sat there and didn’t go anywhere, the States would eventually take you—there was a joke that this category of people was called “trash.”

The way you got accepted was that you had to prove that you were a refugee. It was obvious that most of us were refugees. We escaped by boat, and the way that we escaped proves how horrible it was in our countries—you know, hundreds of people in tiny boats like sardines, and the boats had no electricity, no room. They were designed to travel in the river, and we took them to the ocean. But there were also the fake ones, the criminals, who took advantage of the refugee crisis.

Each country had their own policy for accepting refugees, and the top three were the United States, Canada, and Australia, in that order. They each had a different type of people they wanted to accept. In America, they wanted to take well-educated people, like doctors, lawyers, and intellectuals. Another case was that they would take people who worked for them during the Vietnam War, like high-ranking officers, generals, and people who fought in the army. The special case comes back to Reagan: if you knew any American dead bodies buried in Vietnam, America would send a team there to investigate your claim, and after they confirmed that they found a dead body, the person would be allowed in the States within 48 hours.

I knew of one dead body, but I didn’t have enough information to say exactly where it was. It was in a rural area, so you could not say a street, which made it hard, but I knew of it because my friend told me. It was in a Communist zone, and there was a tombstone. Everyone left it alone to respect the dead.

When we interviewed for America, I didn’t like the immigration officer. He never said hi and he never looked at us, he just looked at our file. And he never talked to us, he just talked to the interpreter, even though he asked if we could speak another language and I spoke a little English and my sister spoke French. He just had a face like he was very mad; he was so tense and not very friendly. At some point, he turned to the interpreter, and said, “Sorry, you’re not accepted. You don’t qualify.” Then, what he did really shocked and surprised us. He had a stamp, and he stamped our file so hard with the rejected stamp that we had to leave the room.

But we were horrified at being stuck in the camp—some people had been there for four or five years—so my sister and I decided that we had to get out of there. It wasn’t that bad at the camp, but the uncertainty terrified me. So, we applied to go to Germany, and we got accepted. After we got accepted, people talked to us and said, “No, you’re not going to Germany!” Because we had just run away from the Vietnamese North and South conflict, so why would we go to Germany for the East and West conflict? We asked ourselves: if the East Communists take over, where are we going to go?

So, when the Australians came, we applied for Australia, but they couldn’t take us because the Germans still had our files, and they had been taken to Kuala Lumpur to process.

Then, when the Canadians came, our files were back. I remember that we went to a room and the Canadian immigration officer, who was around 30 years old, wore jeans and a t-shirt. For whatever reason, at that time, we came in and were surprised that this person worked for the government. We thought they would wear suits, but they all wore jeans and t-shirts—really old t-shirts, too. I remember that his name was Cameron, but I don’t know if that was his first or last name.

He smoked, and the first thing he did was smile at us, so he was really different from the American immigration officer. He even asked us if we wanted water or a cigarette. I smoked, but I said no to be polite, so he apologized for smoking. The interview went really well, and he accepted us. The only problem we had was that I looked older than my siblings, even though I was the second youngest, and that I had another brother in Vietnam who had the same name as me (when spelled in English), because the accents on our names were different in Vietnamese—so we had to explain that.

And then we were accepted to Canada, so we shook hands, and Cameron said, “Okay, you’re not quite there yet, but welcome to Canada.” He was so friendly, and we were so happy that we were accepted, and that’s how I ended up in Canada. Now, after that, we left the Pulau Tengah refugee camp to go to the transit camp, Sungei Besi A, so that they could process our paperwork and we could wait for our flight. It was a whole process.

The first policy for Canada at that time was this: if you were sponsored by the government, like myself, then you were not allowed to come to Canada during the winter. If you were sponsored by a private sponsorship, such as your relatives, then you could come at any time. It doesn’t make sense that there were two policies, but I think they were afraid about our health, and if you were sponsored by family, then your family could take care of you. So, we came to Canada in late March. The second policy was that when you entered Canada, you had to go to Montreal for paperwork before you went anywhere else.

Me in the refugee camp posing in front of a painting during an art exhibition by boat people in the camp. The painting beside me depicting the scene of boat people being attacked by pirates.

So, I left Sungei Besi A to get on a bus, which took us to the Kuala Lumpur airport, where we got on a Canadian airline. I remember that when we got on the airport, all the flight attendants were standing at the door, and they told us, “Welcome to Canada!” and gave us a pin of the Canadian flag. My impression about Canadians when I was on that airplane was that they treated us like kings and queens—but that was just how service was in the West. We came from a war-torn country, so Canadian people were much friendlier. They also knew we were refugees, and I felt kind of guilty about how they treated us—they kept offering us pillows.

I entered Canada on March 27, 1981, with my siblings, and the first city I landed in was Vancouver, British Columbia. We remember waiting there for one hour, and at that time, we got something that they called a yellow paper or immigrant paper. I was surprised, because it was such an important document—even the Canadian government kept saying so—but it was so thin. I folded it and put it in my wallet, and then one or two years later, it was wrecked.

On that paper, it said that our landing city was Vancouver, B.C. Many times after that, we had people ask our landing city, and I kept putting Saskatoon, because that’s where I lived, but they wanted our landing city, which was Vancouver.

From Vancouver, they flew us to an army base in Montreal, which I forget the name of. There, I saw my first snowfall, which was really light, but I wasn’t paying much attention. At the army base, we were served by soldiers, and I thought that wasn’t a bad idea to send us there, since they had a lot of people working to look after us. There were 242 of us.

One of the interesting things that happened there was that we were asked to send our clothes away for them to wash, and we were also asked to shower. They gave us paper clothes, and there was a big bathroom with a lot of stalls for us to use: one side for men, and one side for women. When we lined up, they put soap on our heads, and for what I know, some people didn’t like that—especially the adults. They thought the treatment wasn’t humane. But they made a complaint, and it stopped afterward, and we were given the soap to apply ourselves.

But the first time we showered, I was the last one in line, and I had the soap on my head, and I was sent to a shower stall to wash myself. And when I went in—and I’m not sure when it happened—they had run out of hot water. So, I kept running in and out and in and out, and I thought to myself, “The water in Canada is cold!” But I had soap on my head, so I had no choice but to keep running in and out of the water.

So then, I kept thinking to myself: “Do they actually shower like this in Canada?!” I actually thought that was the case—were Canadians really that tough? It wasn’t until later when I came out and I realized that they had just run out of hot water.

I didn’t know, because when we took our showers, they set the temperatures for us. And it was a new thing to us, in a new country, and we didn’t know how to adjust it ourselves. All my life in Vietnam when I took a shower, it was not warm water. It was just water directly from the river, so I thought that Canadians used the river water too.

After Montreal, all 242 of us refugees were sent all over Canada, but we didn’t know where were going to live yet. The last interview my siblings and I had was with two immigration officers, and they were not wearing t-shirts, they were dressed properly, and they told my family that we were going to live in Saskatoon. We were really disappointed, since we wanted to be in the big city with a bigger community. Most people wanted to be in the big city, and many people were hoping they could go live in Vancouver because we had heard that the weather was better.

When they told us where we were going to live, I just rolled my eyes. “Saskatoon, Saskatchewan?” What the heck was that? It was such a long name. But I remember the immigration officer said at the time that Saskatchewan was the province of wheat and education. At the time, I understood the word wheat, because I came from an agricultural area. I knew a bit about Canada already; I had learned a bit in the camp. But when he said “education,” I didn’t get it. I guess what he probably meant was that Saskatoon has the University of Saskatchewan.

But we were horrified and really disappointed—mostly because I lived in an area in Vietnam called the prairie, and then I ended up in the prairie again. And I could not stand the Vietnamese prairie!

At the time, all 242 of us were scattered all over the country, because at that time, the Canadian government had a policy of decentralization, where they wanted to encourage people to live everywhere. Only 8 of us ended up in Saskatoon, and half of that was me and my family.

So, we got a little bit sad to be in a small city. But we left the army base and got on the flight, and at that time, we were so sick of flying, because we had never flown in our lives, and the last flight was the worst one, I felt like I could die. When the captain announced that were in Saskatoon, I didn’t have to understand English that well to know what he meant. So, I peeked through the window to see Saskatoon from the air, but the fact was that I was on the wrong side of the window, and so were the rest of the Vietnamese people I was with. When we looked out the window, we didn’t see the city, we only saw white. It was still winter!

Click here to read Part II: Arriving and Making a Home in Saskatoon.

Trần Bá Hùng.

BA HUNG TRAN is a self-taught origami artist. He immigrated to Canada from Vietnam in 1981, and has made his home in Saskatoon, SK ever since. Ba Hung Tran learned Origami, the art of paper folding, during his childhood in Vietnam. In Canada he started his home-based business, Tran’s Origami, in 1994 to sell his handmade origami products including origami jewelry, framed origami art, greeting cards, flowers, ornaments, and fridge magnets.

“people stories” shares articles from Folklore Magazine, a Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society publication.